There’s no doubt that generative AI is currently the talk of the town. ChatGPT, Midjourney, and the recently unveiled Sora are blowing peoples’ minds and changing the way they work. But generative AI has become a cause for concern amongst those who are attempting to fight fraud, scams, and influence operations. And that’s what the focus of this piece will be about. What I intend to do is examine each technology – text synthesis, image generation, video creation, and voice synthesis – and determine how they might be used maliciously.

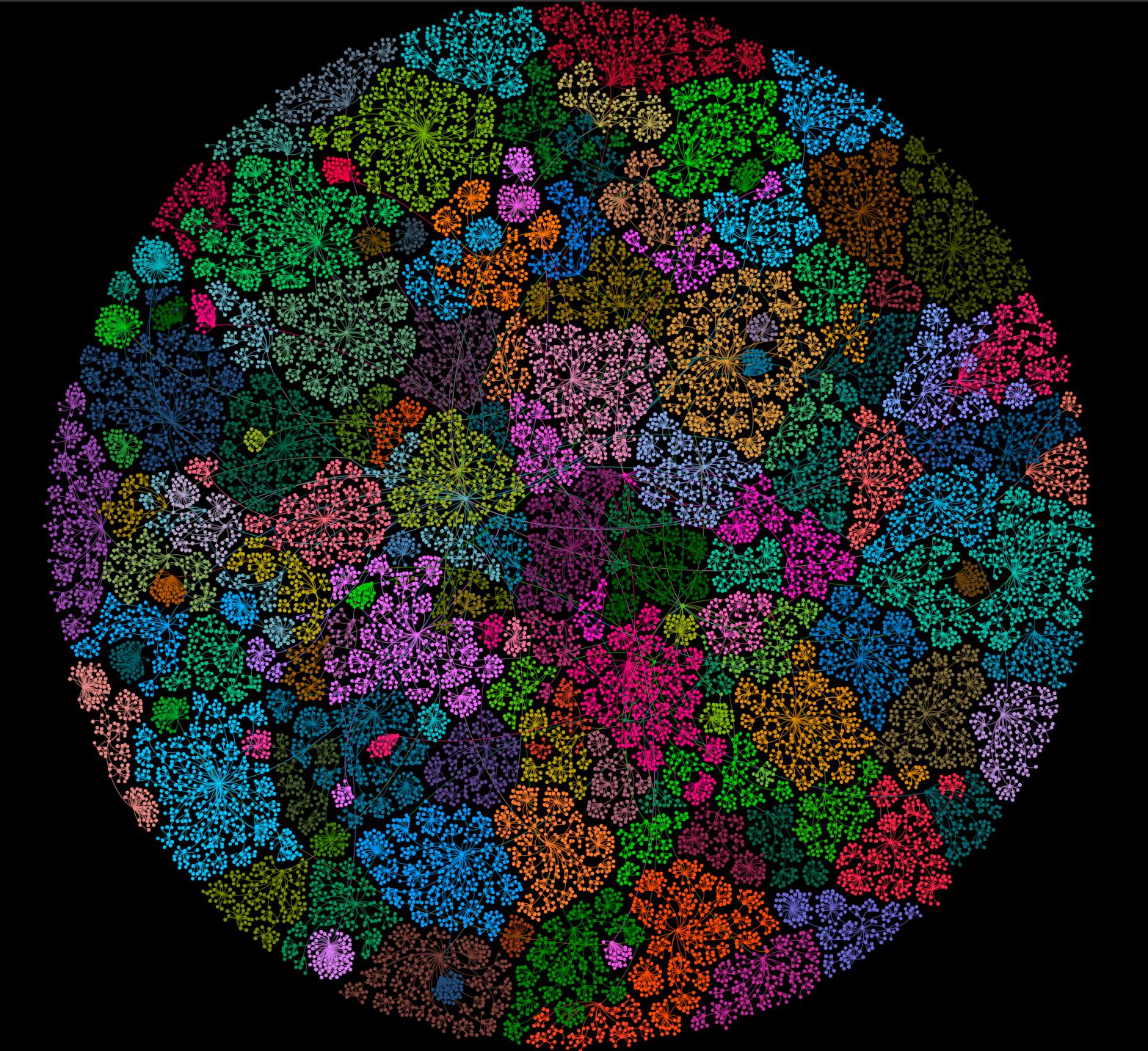

A little about me. I’m Andy Patel. I was formerly a researcher at F-Secure and WithSecure. During the past decade I extensively studied disinformation and influence operations. I examined how they work primarily by analyzing data, and I wrote articles that included pretty graphs like these.

By sifting through reams of data, mostly collected with the now paywalled Twitter API, I attempted to illuminate adversarial tactics employed in social media influence operations. I also spent some time studying the tools and techniques that threat actors utilize. And it goes without saying that the capabilities adversaries have at their fingertips have become exponentially more powerful in the past year or two.

With 2024 being one of the most important election years since the arrival of easy-access generative AI tools, there’s no better moment to understand where we are and how these technologies could be leveraged to perform undesirable actions in the future.

Note that when we talk about influence operations, we’re not just talking about political disinformation. Campaigns designed to influence the way people think can be, and are used for a variety of other purposes including attacking the reputation of a company, discrediting public-facing figures, tricking people into falling for scams, and even duping folks into doing things that are bad for them such as believing the world is flat, self-administering horse dewormer, or eating dishwasher tablets.

With that said, let’s jump straight in and look at everyone’s favorite new technology – large language models.

Synthetic writing

We all know what the likes of ChatGPT are capable of. But before going into how large language models can benefit adversaries, let’s take a step back into the past and examine the tools and techniques they used before generative AI models became widespread, cheap, and easily accessible.

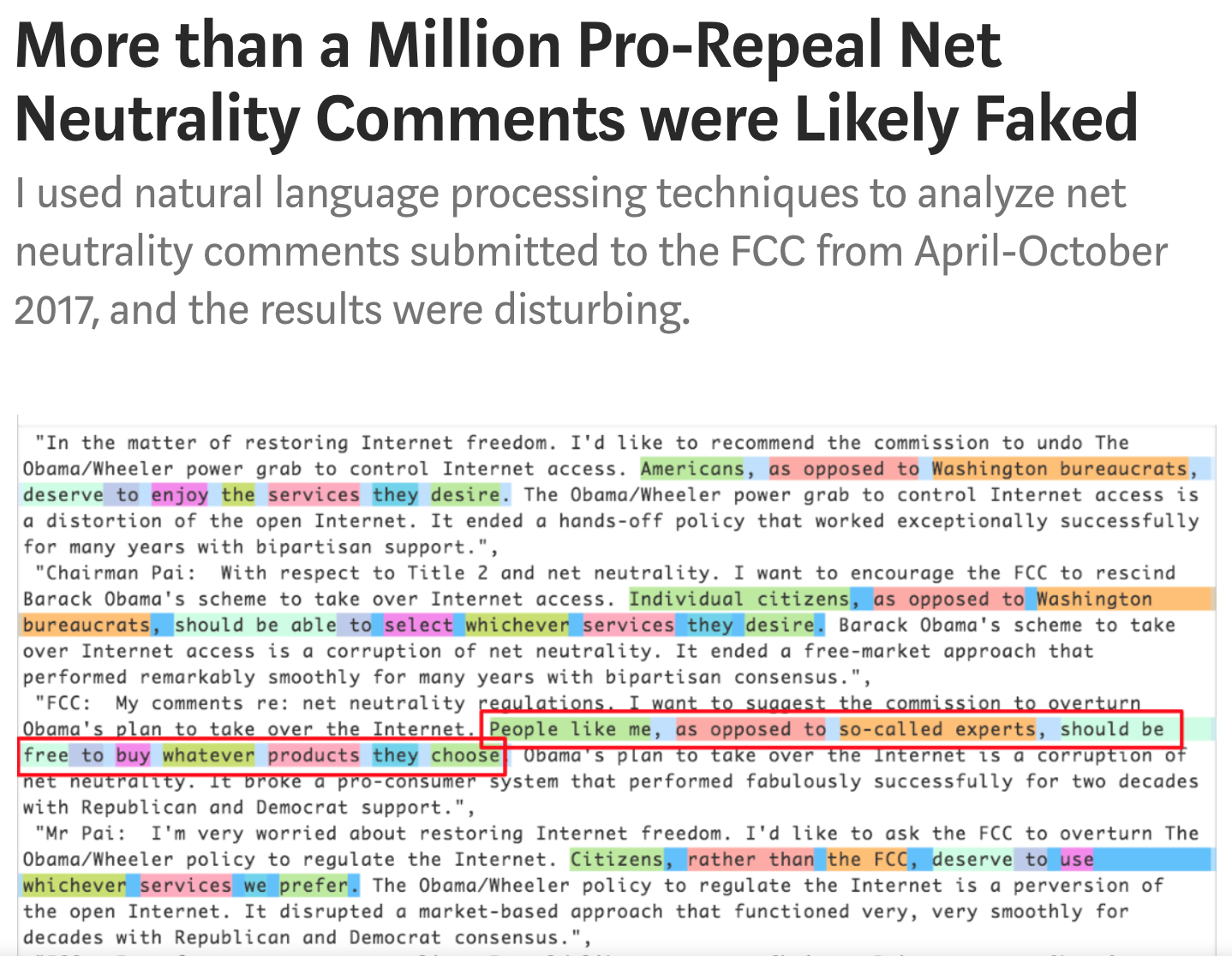

In 2017 a researcher called Jeff Kao discovered that over a million ‘pro-repeal net neutrality’ comments

submitted to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) were synthetically generated.

Kao discovered patterns in the submitted comments indicative of the use of a technique called synonym replacement. Each of the sentences read the same, but contained slightly different phraseology. Look at how, for instance, the green highlighted text in this image changes from phrase to phrase.

Despite the fact that no generative AI was used in this attack, these fake comments passed inspection and were considered legitimate.

A recent investigation into these fake comments revealed that three companies were behind the creation of over eighteen million of the twenty two million comments posted on that site. The companies in question have since been fined.

After reading Kao’s article I performed a quick search and found gray market tools designed to do precisely what he’d described. Here’s one of them – Spinner Chief.

Spinner Chief can perform synonym replacement in over twenty languages and includes functionality to batch-generate thousands of articles within minutes. Interestingly, it still exists, along with a whole host of other “spinner bot” services. And this is despite the fact that large language models can perform that task better. That’s probably because synonym replacement is still a lot cheaper to perform.

The advent of large language models all but invalidates synonym replacement. Provide a large language model with an appropriate prompt and run it over and over to generate unique sentences that can’t possibly be pattern matched.

This technique is also very powerful when considering phishing emails.

Historically, phishing and spam campaigns sent identical emails to thousands of users. Thus it was easy to detect and block them using regular expressions or string matches. With a large language model, it’d be cheap and easy to re-run a prompt for each email sent, thus completely avoiding pattern matching detection techniques.

Here’s another blast from the past. And when I say past, I’m referring to the pre-ChatGPT era.

Yes, people used to train recurrent neural networks to write reviews on sites like Yelp and TripAdvisor. And they’d make money by simply scripting the model to churn out thousands of reviews and then auto-submit them. Yes, folks, this is what we did before transformers and LLMs!

But here’s an interesting question: do adversaries even need to generate unique written content? Not really. Check this next example out.

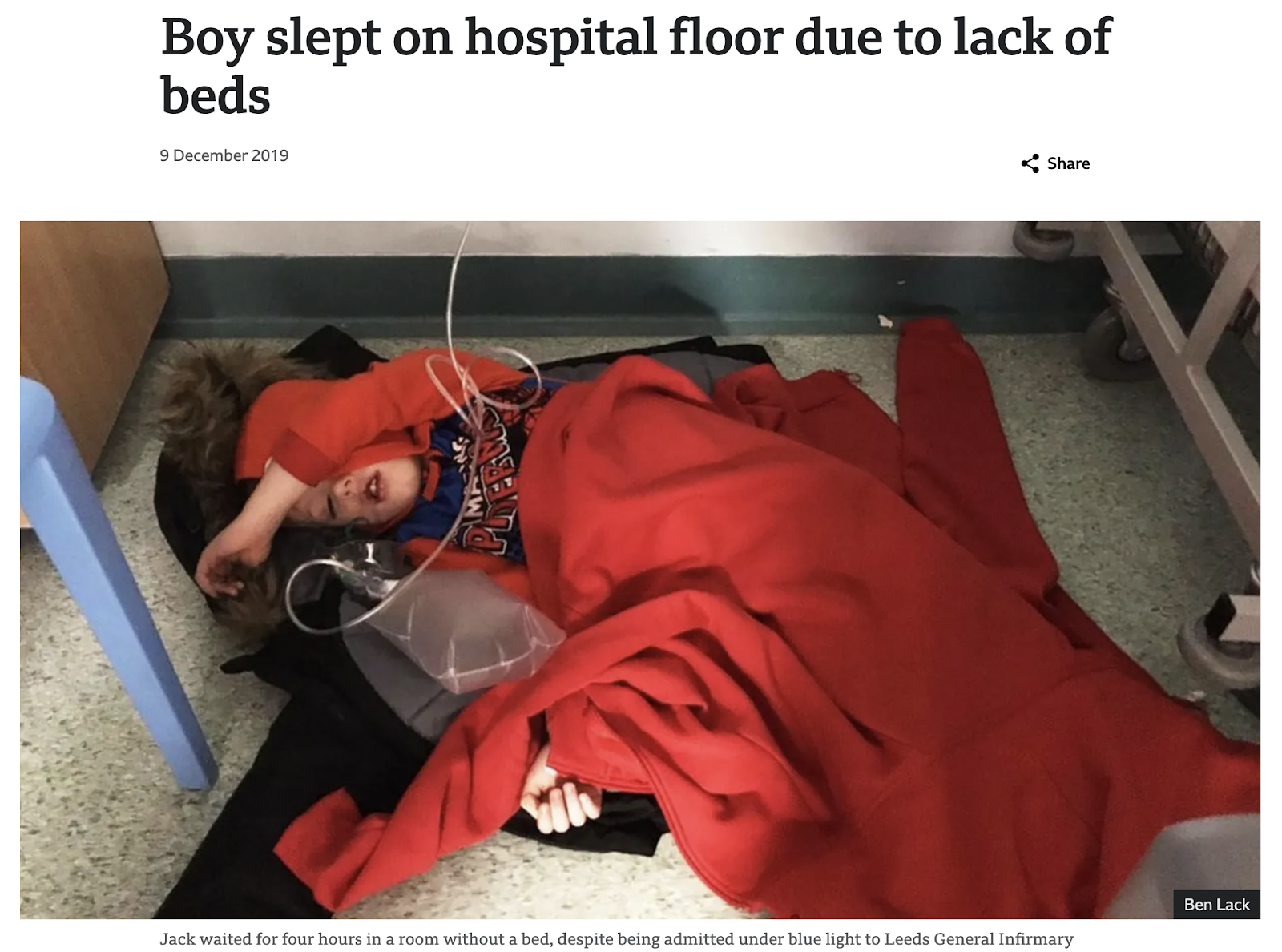

Just prior to the December 2019 UK General Election, a photo of a boy sleeping on the floor of an overcrowded hospital in Leeds spread across the internet. This image depicts an article about the incident that was posted on the BBC website.

During a television interview with Boris Johnson, one reporter produced his phone and attempted to show the former Prime Minister this photo. Boris reacted to the question by simply pocketing the reporter’s phone, and moving the conversation on. Naturally, the clip went viral, and soon after, a slew of random Twitter accounts started posting word-for-word identical replies to threads on the subject. Here’s a screenshot of a few of them.

Naturally, it didn’t take long for folks to figure out that the Twitter posts were identically worded. But that didn’t stop them from altering the public’s perception of the incident.

After the election, people in Leeds were asked about the incident and a majority of respondents believed the photo of the boy to have been faked.

Did you notice anything else about those tweets?

They’re all replies to posts by influential individuals – journalists and members of parliament. This is reply spam, and it works more often than you might imagine. Over the years, many politicians have been led to believe in a lie purely because an adversary directed a sockpuppet army to spam out copypasta immediately after a major event.

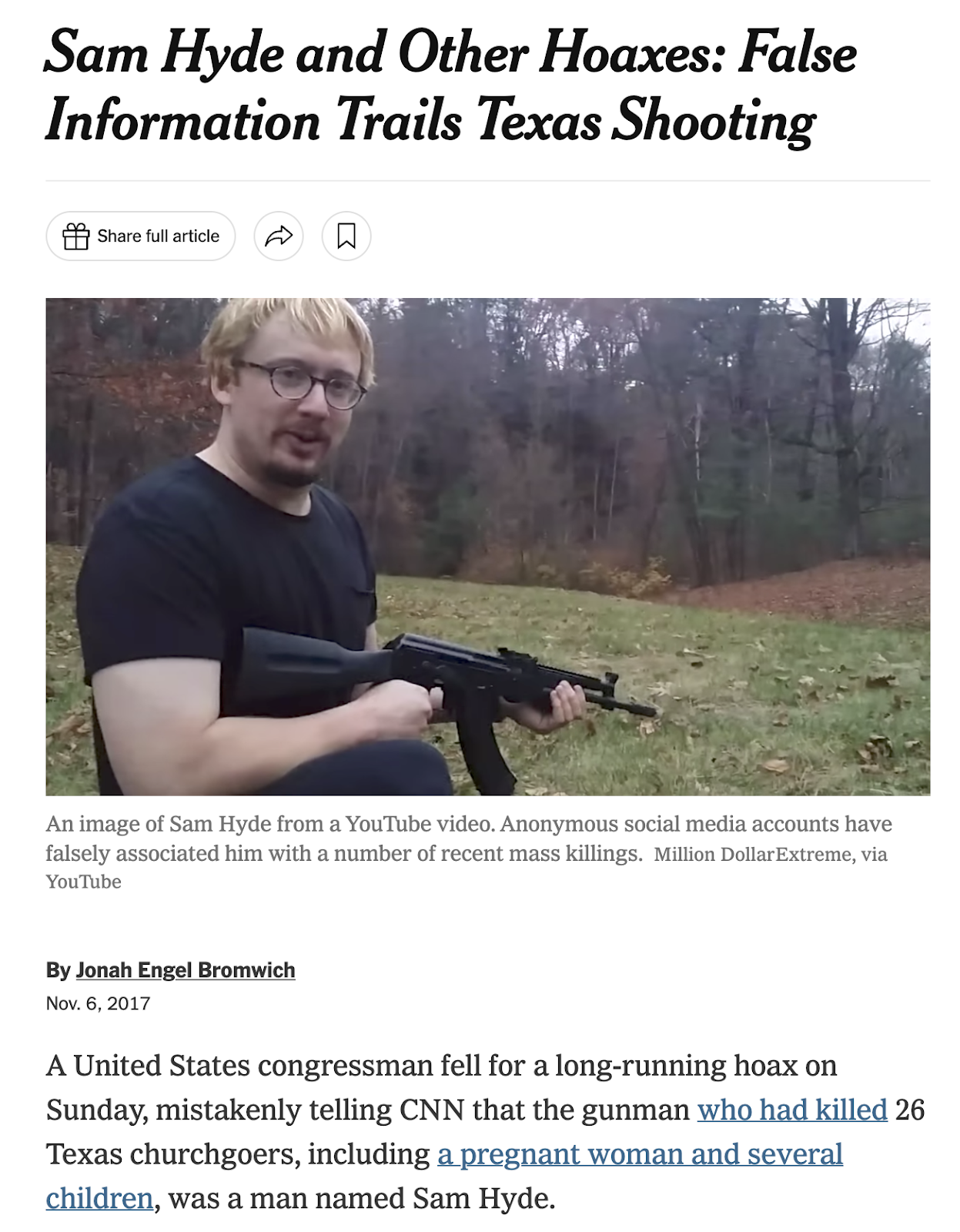

The best example of this might be the 4chan-derived meme of an individual called “Sam Hyde” that is predictably trundled out after any suitably newsworthy mass shooting event.

Copypasta can just as easily be used to propagate scams and fraudulent schemes. I recently examined a network of YouTube accounts promoting crypto currency scams.

The scammers posted copy-paste messages in reply to each others’ videos in order to make their schemes look legitimate and game the platform’s recommendation algorithm. Videos with more likes, subscribes, and replies receive boosted recommendations.

Scale and speed matter in influence operations. And the truth matters not. If you can get people to believe a lie, many will continue to believe it even after it is debunked. They say a lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is putting its boots on. And that’s why generative AI is going to bolster influence operations.

But it’s more than that.

AI will allow adversaries to reach audiences they weren’t previously able to. This is something that’s obvious to me, since I live in Finland, a place with a very difficult language, spoken by a relatively small number of people the world over. Large-scale overseas scams are pretty rare here. Why? Because scammers operating outside of Finland can’t speak the language. And tools like Google translate have typically sucked at Finnish. So, even if an adversary attempted to translate their emails or text messages into Finnish, folks here, on the receiving end, immediately recognised the bad translations and became suspicious.

Newer, better large language models are writing passable Finnish. And this opens up the Finnish market to overseas scam and disinformation operations for the first time in history.

Here’s another thing. In research I performed during late 2022, published as Creatively Malicious Prompt Engineering, I discovered that GPT-3 could emulate a person’s written style. I called the capability “style transfer”. That’s the GPT-3 from late 2022, mind you. Not GPT-4, or Anthropic Claude 3, or any of the newer, more capable models we have available today. With the ability to mimic an individual’s written style, spear phishing just got a whole lot better. Especially if you bear in mind that emulating a person’s written style is a task that would be difficult even for a seasoned writer.

But style transfer opens up something even more sinister. An adversary could use it to insert scandalous fabricated communications into a trove of leaked documents in a hack-and-leak attack.

Remember the DNC hack-and-leak of 2016 that caused uproar regarding Hilary Clinton’s email usage? That stuff kicked off Pizzagate. And subsequently QAnon, Stop the Steal, and the January 6th 2021 insurrection. Now imagine what might have happened if the adversary had fabricated even more scandalous communications and inserted them into that dump.

And think about it. Although the victims of that leak might refute the communications, there’d be no real way of disproving their authenticity. And, well, would it really matter? Whether or not they’re debunked, enough people would believe them anyway.

This sort of thing could easily happen this year, in the lead-up to the US elections. And while the targets of reputation attacks and intimidation campaigns are still typically journalists and politicians, with this stuff getting easier, the scope of those attacks could easily expand in the future.

Large language models allow vast amounts of believable and well-written content to be created in the blink of an eye. From the point of view of influence operations, this is scary. One particularly sinister way this scale could be leveraged is in attacks designed to discredit or harm the reputation of an individual or organization. Fake websites containing reams of articles could be created in hours or even minutes. And ChatGPT could even be used to write the code for those websites. Armies of automated sockpuppets could be employed to spread scandalous rumors on social media sites, just by leveraging a large language model’s ability to write believable looking posts. And those same automated mechanisms could be used to post disparaging remarks in comments sections on news sites and the like. Astroturfing at scale no longer requires an army of humans. And this is why the number of potential targets for reputation attacks may increase significantly.

Imagine you’re the CEO of a corporation waking up to the news that there’s widespread outrage about your company. Multiple fake sites have appeared online, as if overnight, containing falsified rumors about product safety, environmental impact, corruption, employee mistreatment, or malpractice in your company. What would you do about it? How do you even refute it? And if you do, will the public believe you? The whole thing is a PR nightmare. And in Creatively Malicious Prompt Engineering, we demonstrated how to perform such attacks against a company and CEO that we asked GPT-3 to make up.

Let’s not also forget that the original GPT-3 paper was published in 2020. Very few people had access to that technology until the end of 2022, when ChatGPT was released. And I think we’ll find that the cutting edge of these technologies are always going to be a few years ahead of what we have at our fingertips.

But as old as GPT-3 is now, it enabled a multitude of new attacks and gave adversaries a whole toolkit of new capabilities that, frankly, work well enough. The attacks demonstrated in my publication don’t even need a more powerful model than that one. And open source models with GPT-3’s capabilities can now be downloaded and run locally.

How do we mitigate this stuff? It’s not going to be easy. AI will be used to write both benign and malicious content. Thus determining that something is AI-written is not going to be enough to deem it malicious. Spear phishing content is, by nature, designed to look benign – an email asking a colleague to urgently check a presentation they’ll be delivering tomorrow is just as likely to be a real request as it is a spear phishing attempt.

In some cases, determining whether something is AI written might be useful. Fake websites and posts from fake social media accounts are good examples. But you have to find those things first, which means the threat is already out there and has probably already done its job. As I’ve mentioned time and time again in this section, speed and scale matter. Especially in our post-truth society. And if your enemy has already made a lie or rumor go viral, there’s little you can do to fix the situation after the fact.

Moving on, let’s look at image generation.

Synthetic images

It is maybe appropriate to open this section with the oldie-but-goodie GAN evolution image.

And I’m including it not just to remind us of how far AI image generation has come, but to remind us of the fact that one of the first malicious uses of AI image generation was the creation of fake social media profiles.

Here’s one of the earliest reported fake social network profiles that employed a GAN-generated face. It was created on LinkedIn in 2019 and apparently fooled a great deal of people. You can read more about that here.

Sockpuppet accounts with GAN-generated faces have been commonplace on just about every social network platform for quite a few years now. We no longer bat an eyelid when we stumble upon them. And it was probably thispersondoesnotexist.com that really spurred that whole phenomenon to where it is today.

Of course, when we think about AI image generation today, we no longer think about GANs. Stable diffusion is the new hype and services like Midjourney get all the limelight.

The Pope wearing a fashionable Balenciaga winter coat is an interesting example of how AI imagery can easily fool people. When I first saw the picture, I didn’t realize it was AI generated. It was believable because it seemed like a real thing that could have really happened. It wasn’t scandalous or political. Unlike content such as faked images of Trump being arrested in New York.

Synthetic pictures of benign or perhaps even light-hearted phenomena are exactly the kind that might fool the regular person. Here’s one I created with Midjourney depicting a bunch of cats outside 10 Downing Street. Larry presumably invited them over for a lockdown party.

I present this picture to illustrate a point. Although this might look like the front of 10 Downing Street at a casual glance, it doesn’t take long to realize that the image contains inconsistencies. Here’s what the actual front of 10 Downing Street looks like.

By Photo: Sergeant Tom Robinson RLC/MOD, OGL v1.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28014902

Admittedly I only ran three generations with my prompt, resulting in twelve images to choose from. The one I chose contained the most accurate depiction of the building. And yet it includes three lamps, some pillars, and omits the fanned window above the door. Also, the cats are all rather samey.

Interestingly, the number on the door presented real problems for Midjourney. Sometimes it was absent, sometimes it was in the wrong place, and often it was a completely arbitrary number.

Inconsistency in image generation models results in the operator needing to run potentially dozens of jobs in order to create an accurate enough depiction of both the location and subject matter. In my cat example, I would have preferred a variety of different looking cats in addition to a very convincing depiction of the building. And with the outcome being that random, I may have never got what I wanted, even after hundreds of jobs.

However, as I’ve reiterated, authenticity doesn’t matter on the internet. This synthetic image of an explosion near the Pentagon was shared virally on Twitter despite the fact that the image contained inconsistencies that were easily spottable.

Will adversaries use AI image generators to spread disinformation? Maybe. However, the problem with image generation technology currently is that prompting is fiddly. AI art models have an almost uncannily consistent ability to misinterpret your intentions, regardless of how well you describe what it was you want.

And why use an AI image generator when tried and tested non-AI techniques work just fine?

In November 2019, during the run up to a general election in the UK, a stabbing incident occurred at London Bridge. The perpetrator was shot and killed by the police. Immediately afterwards, a photoshopped tweet designed to look like it was written by the leader of the Labour party, one of the main parties standing for office in that election, was circulated on social networks. It looked like this.

Simple. Effective. And not at all AI-generated. This is what we call a shallowfake. And shallowfake images like this one are still commonly used to spread disinformation. If it works, don’t fix it. And this stuff continues to work way better than the newfangled AI stuff we have available to us.

Let us also consider the fact that the cutting edge models, such as Midjourney, have built in filters that prevent them being used to depict things like nudity and violence. Sure, there are unrestricted models out there that could be used to create disinformation, but I have a feeling that the present difficulty involved in prompting these models is a rather large barrier to their uptake by adversaries.

But, from the point of view of fraud, certain image manipulation techniques have a lot of potential.

In recent news, an individual used image generation and face swapping techniques to create a completely synthetic influencer account. He purportedly made a great deal of money with that, and now the phenomenon has gone viral. If you’re on Twitter, you’re probably bombarded with links to stuff like this.

This face swapping technique, which is relatively easy to do, would easily enable an adversary to generate compromising pictures of a target individual, which in turn could allow them to blackmail or phish that person. Simply send your victim one compromising photo and an accompanying link to more like it. The message would probably cause enough alarm that even if the victim knows the images are synthetic, they’ll still be inclined to follow the link while in a state of panic. Ditto for “nudification” tools that are rife on sites like Telegram.

So, yes, AI-enabled image generation techniques do have a lot of potential for malicious use. And while that potential isn’t perhaps as mature as text generation technologies, it will continue to improve at a rapid pace.

And this brings us neatly onto video generation.

Synthetic video

When considering AI video generation techniques, there are two that are worth discussing – generative AI models and deepfakes. Let’s begin with deepfakes.

Technically speaking, deepfake technology is defined as a technique for swapping faces in an existing piece of video footage. Nowadays the term deepfake is used almost everywhere, kinda like how AI used to be used to refer to pretty much any machine learning technique. However, here I’ll stick with the original definition. Here’s one of the most well known examples – a faked video of Zelensky asking troops to surrender.

Aside from the fact that the deepfake in question wasn’t all that convincing, this video is a good illustration of the caveats and limitations of the deepfake technique in general.

So, what do we see in this video? We see an actor with roughly the same build as Zelensky, in clothing we’d typically see Zelensky wearing, speaking from behind a podium. During the video, the actor remains motionless. He doesn’t move about and he doesn’t make any gestures with his hands. He simply reads lines to a camera. After this footage was shot, AI techniques were used to replace the actor’s face and voice with Zelensky’s.

And this, I feel, is the big limitation with deepfakes when it comes to things like political disinformation or perhaps even brand reputation attacks. In order to make a convincing deepfake, certain criteria must be met. You need an actor with physical characteristics similar to the person you’re attempting to mimic. And ideally that actor should be able to mimic the target’s mannerisms – the way they walk, the way they gesture with their hands while speaking, their facial expressions, and so on. Either that or have them stand motionless and speak with no emotion as is the case in the above. And that is ultimately why deepfakes like the one of Zelensky are doomed to fail.

Sure, AI techniques to animate whole body poses exist. But we haven’t yet reached the point where we can viably deepfake a person including all their gestures and mannerisms. But that day will come because things like pose estimation will have a substantial impact on the television and movie industries.

On a final note, let’s consider a recent incident in which a Hong Kong-based finance worker was tricked into paying twenty five million dollars to fraudsters after encountering them on a multi-person video conference call. The story in question suggests that the perpetrators of the scam had access to real time face and voice swapping techniques.

A quick search revealed a github repo containing the code to train a model capable of performing real time face swapping via a webcam. It is entirely possible that this exact technique was used to train models to face swap the fraudsters to the CFO and other members present in the purported multi-person video call. And with twenty five million dollars at stake, it’s not unrealistic to imagine that a group would go to the trouble of doing that. If you have the relevant source material, it probably isn’t all that difficult to pull off.

Let’s move onto generative video to determine whether it will be any more impactful, maliciously speaking.

Just recently, OpenAI released Sora, a text to video model that seemingly blew away the competition. And yes, there are many video generation models out there – Runway, Pika, and Pixverse to name a few. And if you’ve ever tried using one, you’ll know that the amazing examples paraded around social networks are cherry picked from probably thousands of failed generations. I’ve used these techniques to create a few videos of my own that you can find on this site.

Video synthesis is very much still in its infancy. Most models are able to create three second clips at most. And if you’ve generated enough of these clips, you’ll be familiar with the fact that the video often completely loses coherence even within that very short timeframe.

The way I’ve used video generation models is via an image to video technique where I supply an image and explain what it is I want to happen in the video. This allows me to at least define the look and feel of the scene and characters in it. With text to video models like Sora, your mileage will vary considerably. And video generation models are even more finicky with their prompts than AI art models. Which is saying a lot.

I’ve yet to see a clip of synthesized video that could be used for the purposes of disinformation. And I’ve tried making those myself, without meaningful results.

When it comes to misleading video content, tried and tested methods still reign supreme on social networks. And they look like this.

This is an example of an intentionally misattributed video that was shared by a fake news Twitter account during the run up to the 2019 EU MEP elections. The video in question wasn’t shot in Italy, and it wasn’t even shot in 2019. Intentionally misattributed videos like this are still constantly shared on social networks. This is another example of shallowfakes in action.

Given that video synthesis is still very much in its infancy, it’s not worth speculating on when it will be viable for malicious purposes. It’s probably best to wait and watch as it improves. Which I’m sure it will, at a rather dramatic rate.

Finally, let’s examine audio generation.

Synthetic audio

When considering malicious uses of audio generation, voice mimicry techniques immediately spring to mind as those that might be abused. After all, they’ve been abused already. In October 2023, synthetic audio files of the UK Labour Party’s leader, Sir Keir Starmer were released just ahead of their annual conference. One of the audio files purported to capture Sir Keir abusing party staffers. Another depicted the party leader criticizing the city of Liverpool. The audio files were accessed over a million times within just a few days of being posted.

This is not the first time synthetic audio was created for political purposes. During 2023 elections in Slovakia, a fake audio recording emerged of Michal Simecka, the leader of the Progressive Slovakia Party, apparently engaged in a conversation with a leading journalist from a daily newspaper discussing how to rig the election.

While the voices created using synthetic audio techniques aren’t perfect, they can easily be edited to sound more credible. For instance, an adversary can disguise a voice by either considerably reducing the quality of the audio to make it seem as though it were captured from a phone call, or they can add background noise. The faked recordings of Sir Keir, for instance, included background chatter, to appear as though they had been captured in a busy conference center.

Although such techniques wouldn’t fool proper voice forensics, they’re more than enough to fool the general public. And we once again return to the fact that many people will continue to believe the fakes even if they are later debunked.

This brings us back to the Hong Kong case, where both voice and video were purportedly synthesized on the fly. A cursory search reveals that tools able to clone anyone’s voice and perform real time voice synthesis are readily available. In this case, they weren’t even hosted on github, meaning the technical expertise required to use them would be very low.

As such, the Hong Kong anecdote, at least from the point of view of currently available tools and technologies, is entirely plausible. And considering other anecdotal CEO fraud cases, it is likely that these techniques may be used to great effect in all manner of fraud attempts, going forward.

How would one mitigate against such attacks? One easy way is to agree on a verbal “password” that could be used to verify the identity of individuals with the credentials to perform things like large bank transactions. And right now, I’d imagine that conducting calls in non-English languages would also perhaps be a good way to throw adversaries off. Especially if the language you choose to speak in is something rare. Like Finnish.

Voice synthesis is apparently not only very easy to accomplish, it is very good at fooling people. I wouldn’t be surprised if adversaries continue to lean on it in the near future. And I’d be unsurprised if faked conversations play a part in not only fraud but election disinformation, especially this year.

So, where’s all this going?

What we can conclude from this study is that social engineering and influence operations were plenty successful prior to the advent of generative AI. But will AI technologies bolster adversarial capabilities?

Even before the widespread adoption of generative AI, the idea that we were living in a post-truth culture had become pervasive. Soon, the idea of reality may become more sci-fi than science fiction itself. Increasingly powerful reality-replicating generative models won’t just result in specific attacks becoming more effective – they will likely fuel a climate of weaponized disbelief that puts the vast majority of us at risk.

The quality and abundance of fictional content created by generative AI will enhance efforts to drown out the truth. And our ability to determine whether information encountered online is real or fake, especially in real-time, will continue to degrade. This will have cascading effects that will make every attempt at online manipulation – from disinformation to fake news to brand attacks to spearphishing – more potent.

Soon incredibly lifelike images will be generated as quickly as the text in a chatbot. And the flood of these visible dreams will be a shock to reality that will challenge and transform humanity’s ability to process information in real-time. We cannot predict exactly when that moment will arrive, but we know it is coming

Jason Sattler, a former colleague of mine coined a term for the inevitable dawning of a moment when AI images and video consistently reach the photoreality now achieved by the devices we use to document our lives. That term is the “Occipital Horizon.”

Have we reached the occipital horizon yet?

Probably not.

But while we’re not there yet, we get closer to it every second.

Leave a comment